- Home

- Bristow, David;

Running Wild Page 2

Running Wild Read online

Page 2

No sign or sight was ever again seen of Tommy. The spoor of Ironsides was followed across the Shashe into Zimbabwe and out again, but all trails went cold in the shifting Kalahari sands. Other leads were followed to the Zionist settlement of Lentswe-le-Moriti just beyond the foot-and-mouth control fence on the western boundary of Mashatu Game Reserve but they all seemed to be phantom stories. Lions could have taken them, but since no carcasses were ever found it was more likely horse thieves had got them and moved them out of the region.

From time to time stories filtered back to the safari camp about a black pitse, no, not a black-and-white striped pitse-ya-naga, running wild in the Northern Tuli Block (the loose amalgamation of private game reserves and tribal lands usually referred to simply as the Tuli). Long ago, not so long ago, far from here, not so far from here. It was hard to determine which of the stories were of a horse or “wild horse”, a zebra, whether they were fresh or stale, physical or phantom. Zulu became a legendary presence around the Tuli, never entirely corporeal but never completely without substance.

As the search for the missing horses went from days to weeks to months, the safari camp was hosed down, scrubbed, brushed and eventually polished back into shape. The high tide mark was left around the outside of the main building to remind everyone. Someone painted “February 2000” in black lettering above it next to the office door. News that a crocodile breeding farm upriver had disgorged some 2 000 reptiles, ranging from newborns to crusty old flatdogs, into the Limpopo was unsettling. There would be no crossings without rifle cover for the foreseeable future.

Out of all the death and mayhem there was at least one well documented case of life renewed. In the Limpopo delta, people around the world watched on their TVs, fingernails in mouths, as a South African Defence Force chopper let down a rescuer on a winch cable and hoisted a brand new Mozambican mother and her baby girl out of the uppermost reaches of a tree, born in the tree with floodwaters grabbing at the mother’s ankles even as she gave birth.

News hounds following the story to the Maputo general hospital reported back that the baby had been named Rosita. For many years thereafter, dinners at Limpopo Horse Safaris commenced with “Rosita, born up a tree” – bon appetit. Meanwhile, for the ghost horses of Limpopo Valley Horse Safaris there would be some wild times to come.

2

Windmills

THE BLACK HORSE STOOD on a high crest of the Mpumalanga escarpment, the forested scarp plunging away to the Lowveld with the Kruger National Park and Mozambique coastal plain beyond that stretching away, seemingly forever. If you had a telescope, on a clear day you would be able to see a thin dark blue streak that is the Indian Ocean. Huge anvil-head clouds were gathering in the sky over Rhodes Heights game farm and stud. There would be an almighty thunderstorm later that afternoon.

Zulu thought about things, as much as horses can. People who work with them on farms, in yards or mills tend to consider them dullards, willing to do anything any human commands. People who don’t know them well usually appreciate their power and majestic bearing, but don’t think much more about it. But people who work with and ride them for pleasure usually believe that on some level horses are of a higher order, like the Houyhnhnms in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels which rule over the lowly, violent and degenerate Yahoos, the humans.

Perhaps Zulu had vague memories of events that had led to his being here. And now, here, upon this bank and shoal of time, listless and having never really settled back into domesticated life, would he have thought of jumping his life to come?

There had been much suffering and death during those dry times, and yet it had been the only time – other than the time when he had been a pampered foal – when he would have felt really vital and free. And then of course there were the humans, those strange two-legged companions who were beyond knowing to a horse. There had been good ones and not such good ones, but mostly they had been tolerable in the various places Zulu had found himself. They had fed him when he needed food, and taken passable care of him and the other pitses; excepting during the years when he had run wild.

Would he have remembered he’d been born on a farm? He would have had no memory of his mother, a comely yet tough Kaapse Boereperd mare named Ntombi who had died out in the fields while giving birth during a winter storm. It was unlikely he would have known who his father was, one of two feral desert horses from Namibia that had been brought in to bulk up the farm stock. One named Fire established himself as the alpha male in the paddock. The other, Steel, had been foolish enough to try to mate with Fire’s mare and had the weals to show for it.

Bergsig (mountain view) farm was the place where memory would have begun. It was the only cattle and sheep ranch in the area surrounded by fruit and maize farms. Summers on the high-lying grasslands were delightfully warm but winters could be frigid. The district was known for its cherry farms, a fruit that needed a freeze before the fruit would set. For cattle you needed horses, so all the best paid jobs on Bergsig involved riding. Otherwise you picked and pruned fruit trees and shovelled kraal manure.

In spite of his fine lineage, Zulu was born with a defect that was not easy to spot unless you were trained in such things – other than a white paint splash on his shoulder and one white sock that offset his otherwise pure black colouring. The farrier who tended Bergsig’s herd picked it up on one of his rounds. He noticed a bulge around the coronary band at the top of the foal’s front right hoof.

“Little thing’s got a problem with that front foot,” he told the farmer. “See how the right hoof wall does not expand when he puts weight on it.”

“Will it be a problem?”

“It’s like a club foot in humans, it’s called a box hoof. It wouldn’t be much of an issue for a wild horse, but once you add the weight of a rider it could lead to crippling. Generally it doesn’t, but you can tell only when, or if, it does. There’s no point operating but don’t let the children ride him. By the time he reaches three you’ll get a better idea of how things are shaping up, and if he can be ridden after that.”

“What was Mike saying about the little one?” asked Ma nervously when her husband came inside.

“Poor thing’s got a deformed foot.” He remembered the night he’d brought the newborn into the barn, to be kept warm through the night while snow fell outside. For a long time Melodie, who had stayed awake all night with her mother, hugging and bottle feeding the foal in place of the mother that would not be coming back from the storm, would remember it as the happiest day, or night, of her life.

“Oh no,” Ma put her hand to her mouth, “Will it have to be put down? You’ll have to hide it from Senya and Melodie.”

“No, not yet anyway. We’ll have to watch it and see how things go.”

“You know Senya has given him a name, Zulu,” Ma said later over Sunday lunch. Lamb, always roast lamb on Sundays.

“Pa, he’s completely black. And he’s got a fierce spirit like a Zulu warrior,” Senya declared.

“Except for that one white sock and the splotch on his back,” ever-rational Melodie corrected.

The foal was almost completely black but in the African sunlight his coat glistened in iridescent shades of reds and blue-greens, just like the red-winged starlings that nested in the sandstone cliffs beyond the farm.

“That’s a great name,” Ma reassured the frisky 12-year-old boy.

“What about Shaka, the great Zulu king?” offered Pa.

“Another good name for an African horse,” observed Ma, “but I think Zulu will do just as well.”

Pa agreed with his still attractive but farm-worn wife that they could give the little thing a reprieve.

“But no riding until I say so,” he shook his knife at the children and his expression told them this was serious business. “He’s got one vrot hoof and if he is ridden while it’s still growing it will become deformed and then he’ll have to be put down.”

When the freshness of springtime settled on the foothills, the sta

llions on the farm were left to run in the open fields of red oat grass that had made the Highveld so attractive to cattle farmers since time before time. The yearlings and mares were moved each morning from the barn to a paddock beyond the cattle kraal. In Zulu’s second year, with no mother, he was allowed to run with the stallions.

By the time Melodie was 12, Senya had started high school and spent little time at home on the farm. Even weekends were sports times for him. Zulu was going on three and the girl would sneak out with him in the afternoons when she knew Pa was away on some errand and Ma was too preoccupied about the house to take any notice. Or so she thought; Ma noticed everything and kept the peace by letting each member of the family know just what they needed to in order to maintain harmony.

Melodie remembered when Zulu was a foal and so was she. On weekends she and Senya would go out on bitter mornings with their Pa to the barn where the horses slept in winter. Senya’s stunt was to find a fresh cowpat, then jump with his bare, icy feet in the steaming pile. Boys!

Once the sun was up and the frost had thawed, Pa would take out the tackle, shackle up the young black horse and begin the day’s schooling. The idea was not to control the horse too tightly, you needed to restrain it but not to “break it” as was so often said.

“Why would you want a broken horse?” Pa asked. “Would you want a broken car, or a broken wife one day?”

“I don’t know much about men, but I do know all boys are broken,” wise-cracked Melodie. Senya punched her.

Melodie understood and felt that intuitive umbilicus between horse and human. She had her own riding horse, a Palomino she had named after her favourite chocolate. At a notch under 15 hands (15-hh in horsey parlance) Top Deck was a large pony or a small horse, depending on whether you were buying or selling.

For her, Top Deck had always been there, more plaything than pet. It was only when Senya left and she got Zulu all to herself that affection developed into a union of spirits. In truth there wasn’t much work that needed to be done on Zulu ever since the children had frolicked in the paddock with their equine mate. The young horse had imprinted on the two children and they were confidants from day one. Very much unlike that which accompanied the schooling of Fire.

It was like a public holiday on the farm the day Pa decided it was time to ride the wild desert animal. He led the animal out the paddock to the nearby ploughed field while the family and all the farm hands gathered around to watch. With a lot of fuss and what climbers refer to as “tight rope”, the halter and bit were affixed around the stallion’s head. Then the saddle tightened while Fire blew defiance and fury. Two handlers held the horse while Pa mounted. The stallion’s sides flicked and flinched and it was hopping from hoof to hoof like a circus horse.

“Okay, let go …” and off they shot, horse and rider, around the sandy field.

Fire jetéd and pirouetted, did back-arched leaps and dying swan dips. Pa held on, legs flailing, all the time turning the horse in figures of eight. It looked like the rider was getting the upper hand and the crowd was clapping accordingly, when Fire suddenly stopped and dropped to his knees, sending Pa over his head to land on his back in a burst of dust and chaff, still holding onto the reins above his head. Pa lay still while the dust settled and the crowd went quiet. Fire stood up. Ma had her hands to her mouth.

Slowly the man moved his limbs, then rose, one joint at a time, stood, dusted himself off and pulled stalks from his hair and clothes. The horse was standing as though nothing untoward had happened. Pa casually walked up to Fire, then unleashed a power-driving right hook to the side of Fire’s head. The horse whimpered and sunk to his knees, its head in the dirt and open mouth full of grit and wheat stubble. An “uush” went up from the audience.

After some seconds Fire lifted his head, sluggishly, blew dust out his mouth and nose and staggered to his feet. Without ceremony Pa slipped back onto the saddle and walked Fire calmly back to the paddock, dismounted and turned to the amazed onlookers.

“A horse that will not be ridden is no use on a farm,” explained the farmer to the crowd. “It’s in his interests, you’ve just got to explain it to him so he understands.”

Steel, on the other hand, did not get past having a saddle put on him and ended up at the horsemeat butchery.

At the end of that year when Senya was home for the long summer holiday, Pa announced over lunch that it was time to see if Zulu was up to being a real horse. “It’s now or never. You cannot colly-moddle a horse, or a person, for ever.”

“Molly-coddle, Dad,” Melodie snikkered.

“Mel,” he ordered, the tone of his voice hinting at the ignominy of his own limited farm education, “go and ask Lettie to take out some apples from the storeroom.”

What he did not know was that Melodie and Senya had been riding Zulu bareback for quite a while before the appointed day.

“Get it right in the beginning and you’ve got yourself a good riding horse for life,” the father explained while Senya was saddling up the black three-year-old. “Push too hard and you end up with a bundle of horse nerves and colic. Then all you’ve bought yourself is some very expensive horse meat.”

As part of Zulu’s schooling, Melodie had been sharing treats with the bouncy foal from the time it started on solid food. The family’s cook, a rotund Sotho woman named Lettie, played along by slipping her carrots when the youngster told her she was hungry: apples in season, sometimes an extra muffin, or a sugary sweet koeksister whenever she baked.

“Okay, are you ready, Sen?”

“Nah, Dad, let Mel ride him. They are in love with each other.”

By that time the 15-year-old Senya preferred to ride Tommy, a big chestnut that suited him far better than “clunky old Zulu”. Just the thought of that misshapen hoof had been enough to make the boy spurn the black Boereperd-cross. Pa had found the young but imposing 17-hand chestnut at an abattoir in a stall awaiting the glue pot and brought him home. He was a large but gentle beast, not too bright but perfect for a growing lad.

“He’s more my kind of horse. I wouldn’t want Zulu to wimp out on me.”

Melodie glared at him. That was her older brother taking out insurance in case they had injured the young horse before his appointed day.

“All right then, you go and ask Lettie for apples. That should at least help to sweeten the deal.”

Lettie was typical of the Sotho women who worked on farms across the Highveld, wide of beam and larger of heart. She’d said her name was Lettuce but Ma had changed it from the day she started in the kitchen before the children were born. White farm children all grew up on the backs of black women like a Lettie, Patience or Beauty.

“Teta, teta, Lettie, (if the maid was a Zulu), or “Pepula, pepula, Lettie” (if she was a Sotho) were among the first words they learned, raising their short fat arms upwards to be lifted onto the comforting back of their black nanny and wrapped snugly inside a thick Basuto blanket.

Lettie’s real name was Lentswalo but she never shared it with white people. Few thought to ask. Lettuce was the short-straw name she’d drawn on her first school day at the mission school. Still, she loved the children from day one and they loved her back. They spent almost all of the days of their early lives in her company, preferring to eat putu and nyama – maize porridge with meat and gravy – on the rough floor of her small, smoky hut, than indoors with their fussy-pants parents. Best was in winter when snow covered the distant peaks.

That was also the time when the grass withdrew its nutrients below the ground, into the roots. The frost-bleached grass scored bare feet like the barbed wire strands that left all farm children with scars. Senya and Melodie would be up before the birds with blankets and bridles, Melodie’s pockets bulging with crisp apples.

In the small orchard behind the farmhouse, beyond the vegetable garden, grew peaches, plums and apricots, but best were the small, tart red-and-green heirloom Hugo apples. They had been planted by the legendary Groot Oupa who had mollycoddled the seedling

s up from the Cape on the back of an ox wagon.

Except in cases of extreme cruelty, no horse ever refuses its rider. They will not flinch in a hail of arrows or even cannon fire, riding into the jaws of death, the mouth of hell if asked. When horse and rider move as one, when their senses are tuned into the same weft and warp of the landscape, the horse will take them through or over any veld furniture. It makes for a happy horse and a happy rider.

But some horses are never “broken” in the sense that trainers use the term. A broken horse is a broken spirit as well. During Zulu’s third summer on Bergsig, just when he was coming of age, Steel started playing up. Deprived of the desert freedom and cut off from the farm mares by Fire, he wouldn’t let anyone ride him, cantering and wind-sucking around the field. Then he started cribbing, chewing the fence posts of the paddock as well as his stable door at night, much like a human chain-smoker.

“Stall vices,” said the vet. “I see lots of horses doing it. Boredom. He’ll wear down his teeth. Get colic …”

Both of which he did. When he started biting himself Pa took action. Late one summer evening, with purple clouds sneaking over the grasslands, when the horses were corralled back into the barn, there was no Steel.

You might dispute their intelligence but no one who knows them well would deny that every horse has an abundance of free will and playfulness. Yet they are so fast to please. They will ride hard, for days or weeks if need be, as far as their rider pushes them. Like the golden bay Somerset who, back in 1842, carried Dick King from Durban to Grahamstown, 1 000 kilometres in just 10 days across hostile territory, crossing around 100 rivers in order to raise the alarm and save Port Natal from falling into Voortrekker hands.

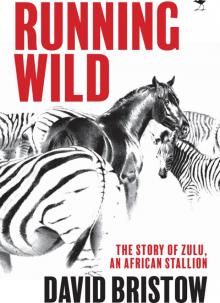

Running Wild

Running Wild